In September of 2022, the Chouinard family—lead by Yvon, the patron saint of ethical business—made headlines last year when they donated their $3 billion family-owned business.

In a letter to customers, Yvon explained “100% of the company’s voting stock transfers to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, created to protect the company’s values; and 100% of the nonvoting stock had been given to the Holdfast Collective, a nonprofit dedicated to fighting the environmental crisis and defending nature.”

Despite the myriad media coverage of this unprecedented move, it really shouldn’t come as a shock. Patagonia has long-led the socially-conscious business movement. However, they haven’t always been the perfect paradigm of the triple-bottom line. And it’s helpful for other aspiring socially and environmentally-conscious businesses to understand and honor the long and non-linear path Patagonia has taken to become what it is today.

That story, of success and failure is summed up in Yvon’s Let My People Go Surfing.

The Patagonia founder chose to subtitle this book—”The Education of a Reluctant Businessman.” Sometimes surly, sometimes self-deprecatingly humorous, but always spirited, transparent and inspirational, this book is worth as many rereads as it has pages. Every line is built on decades of lessons learned and wisdom collected. Even the carefully chosen photos convey a wealth of visual knowledge.

Here are a few big takeaways from this great read and from the history of the company which inspired it.

1. Patagonia didn't start off as an environmental angel.

Contrary to current popular belief, Patagonia isn't some triple bottom line Athena. It didn't spring fully clad and ready to fight out of the environmental movement of the 70s. Their origins are actually much sketchier and their journey has been anything but a unbroken line of upward environmental and social progress.

Patagonia began in the late 1950s as a climbing gear company, Chouinard Equipment. The entire goal of this make-shift enterprise was to earn just enough money to afford its semi-nomadic, self-styled "dirt bag" founders another season of mountain climbing. The roots of Patagonia were naive and destructive. Their primary products were steel pitons--spikes which are hammered into rock faces to secure climbing ropes. After several seasons, however these popular Chouinard pitons began to litter many iconic, and previously unmolested, mountain faces.

"After an assent of the Nose route of El Cap, which had been pristine a few summers earlier, I cam home disgusted with the degradation I had seen...Pitons were the mainstay of our business, but we were destroying the very rocks we loved."

- Pg 26 , History

This degradation of the wild places these pre-Patagonia pioneers held sacrosanct was the first in a half century of ah-ha moments. Seeing the damage their prize product was creating, the fledgling outfit switched to producing and popularizing clean climbing chocks, which could be removed after a climb.

Over time they branched out to other equipment and apparel, eventually spinning off into the Patagonia collection of companies we recognize today. Each of which has been infused with the ethos of conservation and quality. Now, Patagonia would never consider making any piece of gear or equipment without endeavoring to fully understand and mitigate the negative impacts it might create. (Though by their own admission, they are still far from perfect.)

The important takeaway is that even a myopic little shack-based climbing company can, with intentionality and perseverance, become heralded as the gold standard in ethical corporate behavior. Patagonia wasn't exactly green, or just, or visionary from the the get go--though its founders did hold some of these values. They became that way though more than 50 years of striving to be better. And if they can not only learn to adapt but to thrive in the process, no one else really has an excuse.

"When we act positively on solving problems instead of ignoring them or trying to find a way around them, we are further along the path toward sustainability. Every time we've elected to do the right thins, it's turned out to be more profitable."

- Pg 194, Environmental Philosophy

2. Patagonia has f*cked up a lot more than they've succeeded.

As a company, Patagonia has often been on the vanguard of the social and environmental business movements. And while today, their brand in inextricably tied with these ideas, it's taken a lot of trial and error to get there. And like most great scientists, many more of their experiments ended in failure that success. But these failures led to a deeper understanding of fundamental principles, which in tern led to greater triumph.

Patagonia's forays into onsite child care really highlight this. As part of a much needed building expansion in the mid-80s, the growing company embraced open floor plans, cafeteria dining, flexible hours. They also opened the Great Pacific Child Development Center, Inc. (clearly they've always been drawn to grandiose names...).

Malinda Chouinard was one of the primary driving forces behind what was at the time a very novel concept. Providing onsite child care, along with maternity and paternity leave--really including an overall focus employee's families--led to much trial and error. The learning process was "one fraught with laws and hysterical parents," according to Malinda.

However, the team persevered, brought outside knowledgeable voices into the conversation, calmly navigated more than one "open rebellion," and eventually succeeded in creating a truly-family oriented work place which met the needs of their people. A work place which today continually appears toward the top of many "best places to work" lists. In a 2016 Fast Company piece, Patagonia’s CEO explained how the company recoups around 91% of these costs annually, while experiencing a 25% higher employee retention rate than the rest of their industry.

"As the years role by, some of our original day care kids have become parents and employees and our policies have become federal law."

- Pg. 52, Malinda's View of Child Care

Though the still privately-owned Patagonia has often been profitable, theirs also hasn't been a pretty graph of rising profits. In the early 90s, the company was struggling under the weight of its own once meteoric growth rate. A series of challenges eventually led Patagonia--a company which had never before laid off a single employee--to let go 20 percent of their staff go in a single, dark day.

This led to some deep soul searching about the nature of growth, the direction of the outdoor apparel industry, and the purpose of Patagonia itself. It also led to a pivot in the vision of the company, one which transformed them from a clothing manufacture with above average quality and ethical standards to something more. (See takeaway three below.)

Over the years, Patagonia tried, failed, and tried again on issues from employee benefits to sourcing to growth to new business models. But the through line is that they always kept trying. Let My People Go Surfing is really a story of proud failures. Proud not because of the failures themselves, but because of the company's ability to stay the course and eventually create transformative solutions.

The take-way here is obvious: screw up as many times as you need to as long as you keep showing back up. To paraphrase Simon Sinek, the only way to "loose" this game is to choose to give up and leave it. Keep playing long enough and eventually any obstacle can be overcome, especially if your mission is just.

3. Patagonia's beloved clothes and gear are just a byproduct.

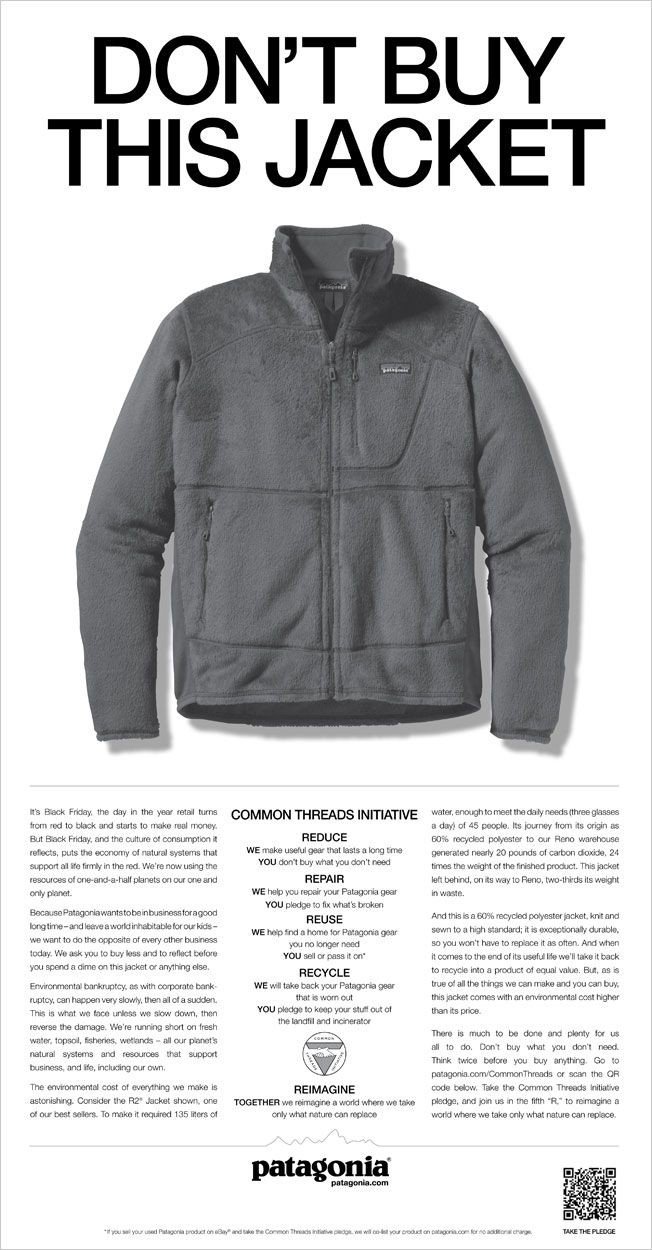

Maybe Patagonia’s most groundbreaking advertisement.

The biggest misconception about Patagonia is that their primary product is clothing or gear. These are important, but ultimately ancillary, to what they actually produce.

The immediate result of Patagonia's growth crisis of the 90s was a lot of tough conversations. From these eventually emerged an internalized commitment to intentionally using their business as a proving grounds and model for others.

"Our mission statement reflects this evolution by saying we will 'cause no unnecessary harm,' and ends with our resolution to 'use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.'''

- Pg. 187, Environmental Philosophy

The company was no longer interested in the allurer of unchecked expansion and growth for growth's sake. They were also no longer content to support conservation efforts via philanthropy and to make positive changes in their business when time and circumstances allowed. They decided to deeply examine their own harmful practices and policies, and to slowly transition them to regenerative ones.

Initially these were painful threads to tug at and their jackets soon unraveled into quagmires of confusing supply chains and damned if you do damned if you don't choices. But their dedicated employees realized that they weren't solving these problems to enrich a single product, company, or single supply chain. They were working to solve social and environmental problems for their entire industry. And for other industries which were watching. They were solving sticky problems for their allies, their competitors, their producer and suppliers, and for an untold legion of new businesses which didn't even exist yet.

It's a journey they are still--and will always be--on.

84-years-young and still learning.

The takeaway, while certainty not a new one, is a powerful one: purpose matters. Anybody can produce board shorts. Sure Patagonia's are often of superior quality, but they're not always the best. Others can and do compete with them along these lines all the time. (And frankly, top-notch topstitching isn't all that exciting--at least for this humble clothes wearer).

But the fact that a major clothing company is ready and willing to incur huge cost and risk to help produce less water-intensive organic cotton or to engineer hats out of discarded fishing nets is huge. And the fact that they are excited to turn over this knowledge and instruct others in these hard learned tradecrafts, is revolutionary.

"It really is the small private business we hope to influence. It is the tens of thousands of young people who dream of owning their own farm some day. All of us working together can create the change we need."

- Pg 222. Environmental Philosophy

--

For many, Let My People Go Surfing falls into the category of obligatory mission-driven business reads. However, it also sits collecting dust on many book shelves. Many folks flipped through it a decade ago in order to say they've read it. Admittedly, we only purchased my copy a few years ago. It was at their Chicago location during their ground breaking Black Friday feat of giving away all profits from that behemoth shopping day.

Our copy now sits dog eared, heavily annotated, and flush with post-it notes back on our bookshelf, but never out of reach.

So if you have a copy, please pick it back up and give it a reread. If you don't have a copy, you can come borrow ours. (Our only ask, as is the case with all our books, is that you write in it; add a little more to the book than when you found it.) Enjoy its stories. Scrutinize its lessons. Mark it up, beat it up, eat it up.

We get the feeling that would make a certain "dirtbag" reluctant businessman proud.

Said “dirt bag.”